J1407b

A giant exoring system orbiting around a young star

J1407 is a nearby young star that underwent a complex series of eclipses that lasted for almost two months in 2007. Our best explanation is that an (as yet) unseen massive substellar companion with a giant ring system passed in front of the star, causing the eclipse (Kenworthy & Mamajek, 2015). We haven’t seen another eclipse towards J1407 (or its full name, 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6), but data from the ALMA telescope array has detected what might be the dust making up the rings themselves.

We now give a brief history of what we’ve done since the discovery was announced in 2012.

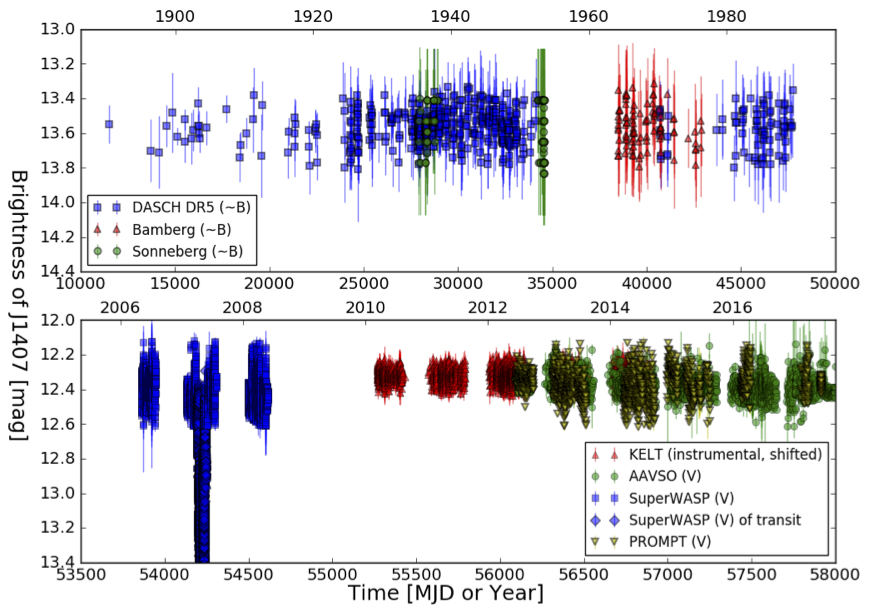

Mark Pecaut, a then graduate student under the supervision of Eric Mamajek at the University of Rochester, discovered the unusual light curve towards the end of 2011. Mark was looking at the light curves of young stars as part of his thesis research. It is difficult to determine the ages of most stars, so several different pieces of evidence are needed to confirm a young star. Looking through the public light curve database of the SuperWASP collaboration, he found 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6, a star almost the same mass as the Sun, with a light curve that showed a 3% variability that repeated every 3.2 days, almost certianly due to fainter star spots on the surface of the star rotating in and out of view as the star rotated.

J1407 showed a very long lasting eclipse event from April through May 2007, where the star’s changed brightness on a nightly basis, sometimes as much as 95% of the flux was blocked by something moving in front of the star. The discovery paper (Mamajek et al., 2012) contained a simple model including four large rings about 0.6 au in diameter surrounding an unseen substellar companion, called J1407b, which orbited around the parent star.

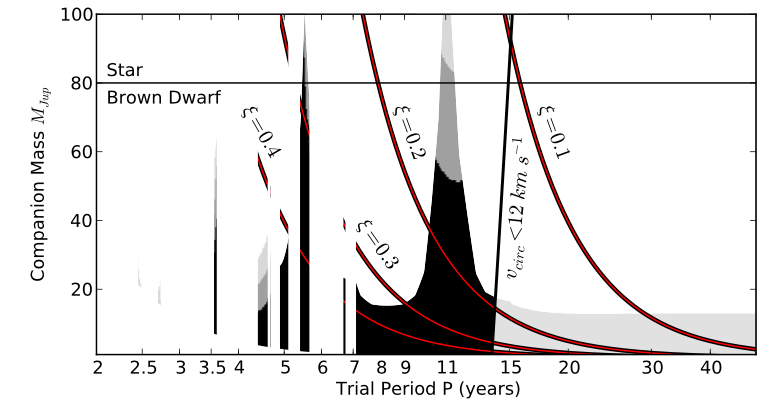

Follow up observations were carried out to try and detect J1407b, which must be several tens of Jupiters in mass in order to keep such a large ring system held together and not ripped apart by the gravity of the star. These included looking for another eclipse in other photometric data (no other eclipses were found), looking for the reflex motion of the star as the gravity of the unseen companion tugged on it (the star is young and is very active, preventing the method from being sensitive enough), and directly detecting the thermal glow of the companion itself (no - even with the largest telescopes and an optical trick called sparse aperture masking we did not see anything).

All these non-detections were still useful, since they allowed us to rule out possible orbits and masses for J1407b, detailed in (Kenworthy et al., 2015).

One interesting conclusion we had was that there were no circular orbits for J1407b since we needed to explain why the ring system seemed to be either very big or moving very fast in front of the star, implying that it was in an orbit close to the star. This presented one big problem: our ring system seemed to now be very large indeed, so large that the rings would spill away from J1407b and fall towards the star. Putting J1407b on an elliptical orbit seemed to make the problem even worse.

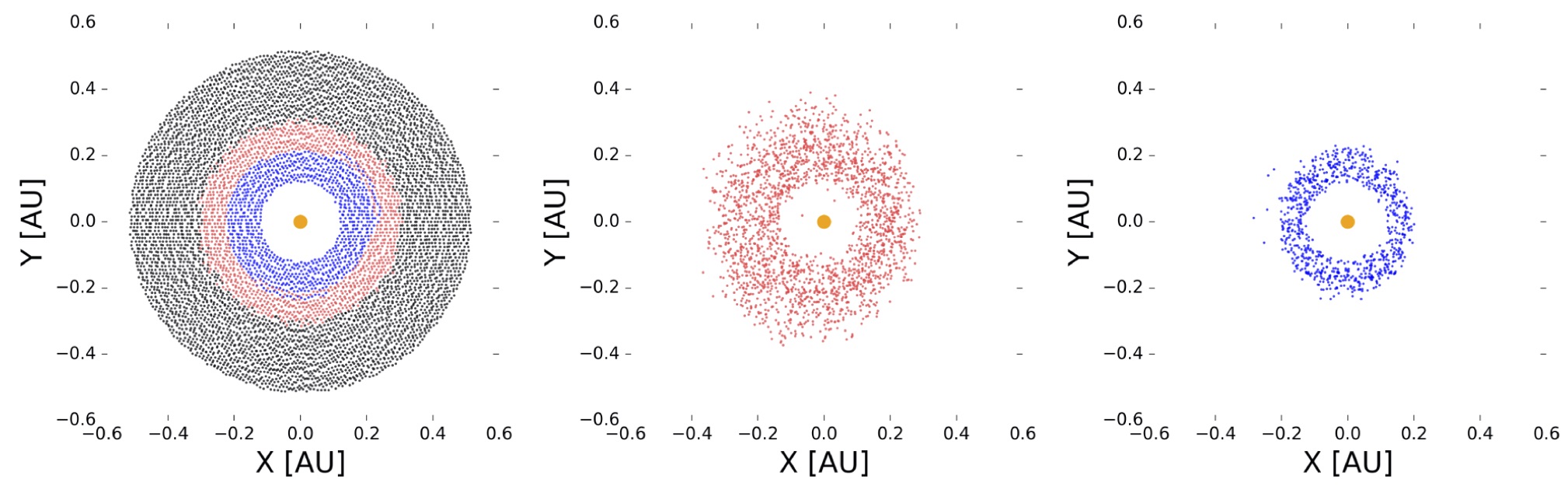

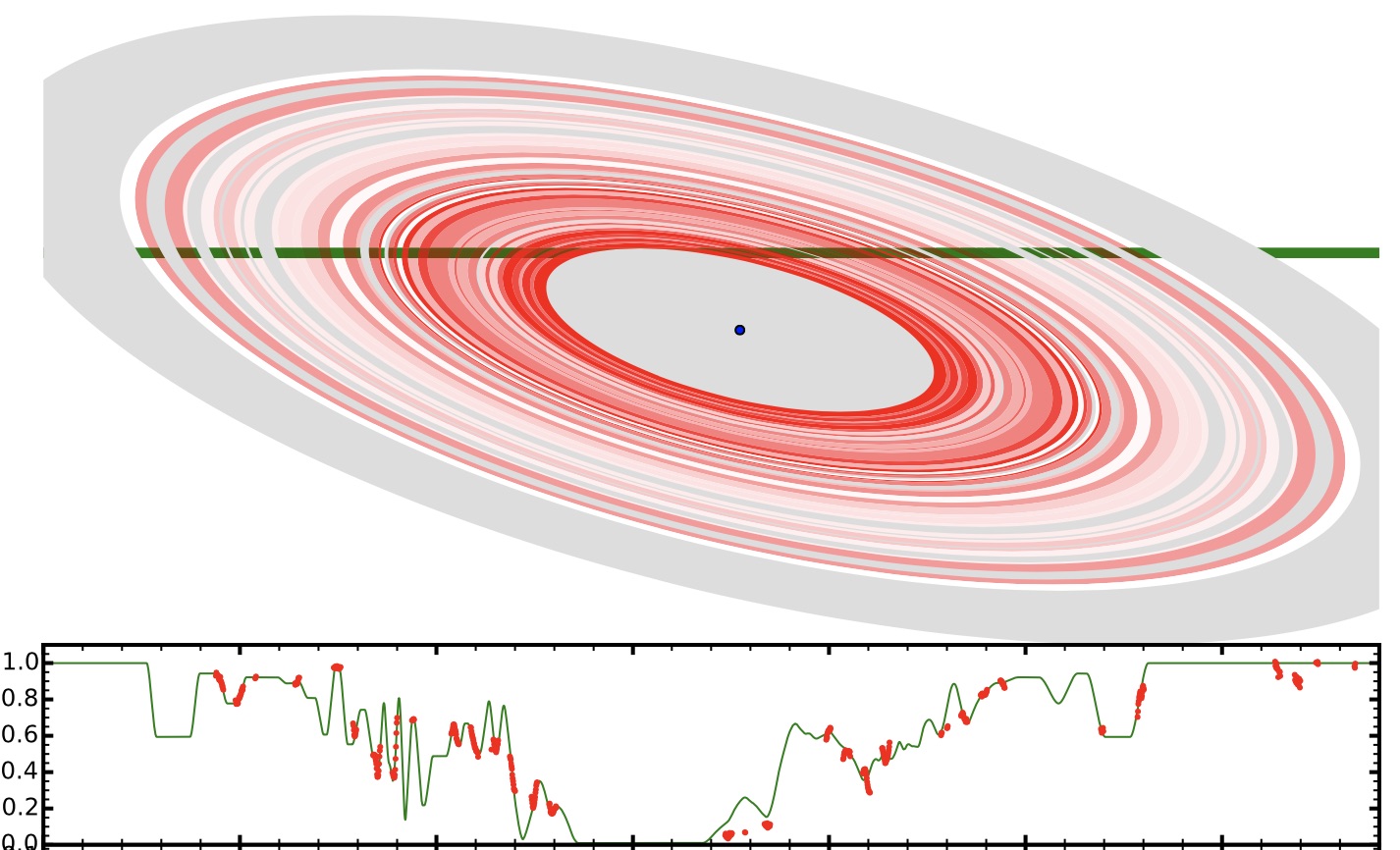

This inspired Steven Reider to simulate a ring system around a planet that itself was in an elliptical orbit around the star J1407 (Rieder & Kenworthy, 2016). The new trick was one of a simple spin - if the rings were added so that they span around J1407b in the same direction that the planet orbited around the star (called prograde motion) then the rings fell apart within a few orbits when the planet passed close to the star.

However, if the rings were spinning in the opposite direction (a retrograde motion) then the rings held together for a much longer time, so much so that we could find possible masses for J1407b and orbital periods that would work!

Even if these orbits worked, then another problem presented itself, in that the rings were tilted with respect to the orbital plane of the planet. Most planets rotate, and the centripetal force generated by this rotation causes the planets to bulge out along their equators, distorting them from ideal spheres into oblate spheroids (M&M or Smarties if you like candy/sweeties). This deviation from an ideal sphere means that any ring system orbiting around the planet will tend to align with the plane of the equator, as is the case with Saturn. Since J1407b is younger and more massive than Jupiter, the bulge around the equator is proportionally much bigger, marshalling the rings into this plane.

The rings of J1407b are about 200 times larger than Saturn’s rings, and for the rings a long way away from the planet, the tidal forces of the star J1407 will force them down into the orbital plane of J1407b, some 20 degrees away. The rings should no longer be flat, but have a large systematic warp to them, as calculated by Zanazzi et al. in 2017.

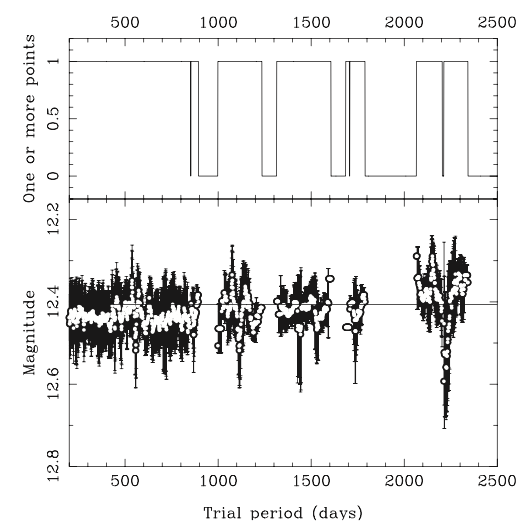

Photographs of the night sky have been taken for over a century, and one of the largest collections is at Harvard University. These photographic plates are being scanned in digitally and published onto the internet through the DASCH project. The process is slow and time consuming, especially as you work towards the Galactic plane, where there are far more stars crowded together and disentangling the signals is challenging, but they reached the location in the Galaxy where J1407 is located around 2017. This enabled the baseline for the J1407 lightcurve to be extended back to the 1900’s, but still no eclipses were detected. The coverage of the photographic plates from DASCH were combined with others from Sonneborg and other more recent all sky surveys that looked towards J1407, but still a null result (Mentel et al., 2018).

Meanwhile, the star is being observed every clear night by the dedicated observers of the AAVSO. They watch J1407 for when the next eclipse will start. The constraints they provide rule out successively more obital periods, leaving J1407b with fewer orbital periods to hide in.

If the planet J1407b could not be detected, then how about looking for the rings directly?

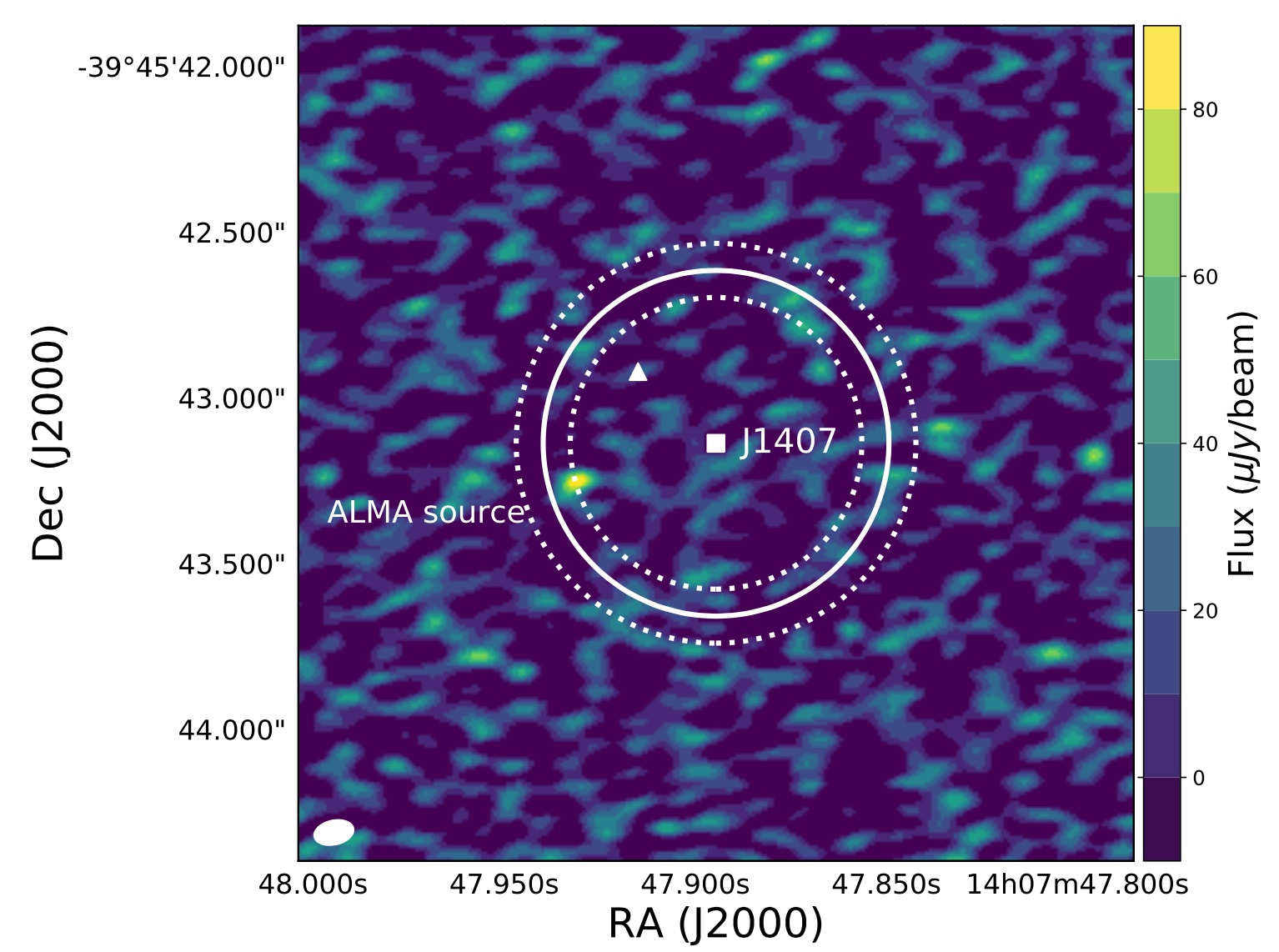

The rings are probably made of small rock or icy particles, ranging from one micron in size up to rocks and boulders. The surface area of the dust in the rings is vast, so much so that they radiate thermal energy at millimetere wavelengths that can be detected with radio telescopes on the Earth. The most sensitive sub-millimetre telescope is the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) in the Atacama desert in Chile. We were able to get observing time on this array of telescopes in the Summer of 2018, and to our surprise we detected a sub-mm source with the brightness we predicted for J1407b’s rings (Kenworthy et al., 2020).

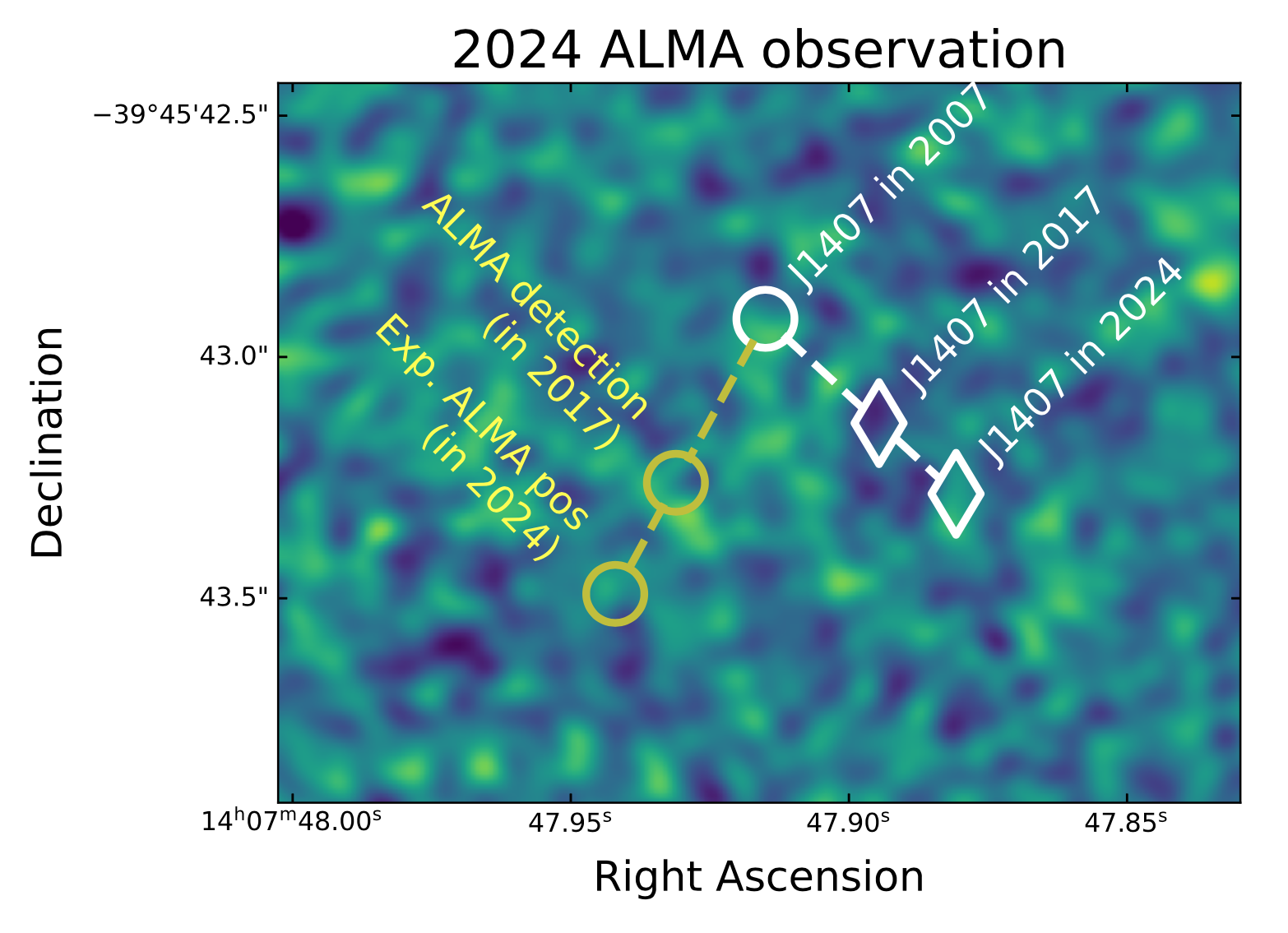

After our initial joy, we then became confused again - because the ALMA source wasn’t exactly in the same position as the location of the star. At these very long wavelengths, the star J1407 is not visible in ALMA, so we had to calculated the expected location of the star and compare it to the ALMA source. If the source is the same physical object that caused the eclipse in 2007, we run into a big problem - the source cannot be in a gravitaionally bound orbit around J1407…. but there’s an very unlikely alternative explanation - that the object we called J1407b is floating freely through the Galaxy, and just happened to pass in front of a very young star.

This is very, very, very unlikely to happen, but there’s a first time for everything…. and to confirm this tantalizing idea, we needed another image from the ALMA array. And in 2023, we got our wish granted! Thanks to a successful ALMA application and a suggestion by the ALLEGRO team, we obtained a second ALMA image looking towards J1407 in 2024.

Unfortunately we didn’t see the ALMA source again, despite having the sensitivity to do so (Klaassen et al., 2025).

This does not mean that the rings aren’t there though - looking for the rings in ALMA was always a long shot, because we’d only be able to detect the most massive (and flared) ring models due to the distance of the system. The rings are still there, just not detectable with these ALMA observations. Our best guess for the 2018 detection is that it was a noise spike or some distant transient source. That’s pretty a unsatisfying explanation, but without more data we’re going to leave it at that.

So that is the latest and greatest information about J1407 and the ring system around J1407b. We still think that the eclipse in 2007 was caused by something orbiting J1407, and that one day we will see another eclipse that will confirm the incomplete light curve from 2007. Once we see it, all the geometry of the ring system is solved almost immediately. Until then, we tide ourselves over and patiently wait for a triggering signal from an observer who says “This star has started fading again!”