Unsolicited Advice

People often ask me if I (cough) have any words of advice for young people.

- On why you should have a professional research web page - If nothing else, your current email and research position.

- On backing up your research - Make sure your hard work is all backed up safely.

- On being professional - Acting responsibly and being a reliable collaborator.

- On registering your astronomy and reduction software - A checklist of what you should do you with your software and data reduction scripts.

- On how to watch a meteor shower - It takes some preparation and a little patience.

Write a professional web page

...so that other professionals will find you.

Hi. Either a fellow researcher or I have pointed you to this page. If you do nothing else:

PLEASE make a web page and put your email address on it.

There, that's it. Simple, really.

If you are willing to read a bit further, I'll show you an example of the minimum you should put on it, and after that, I'll give the reasons why.

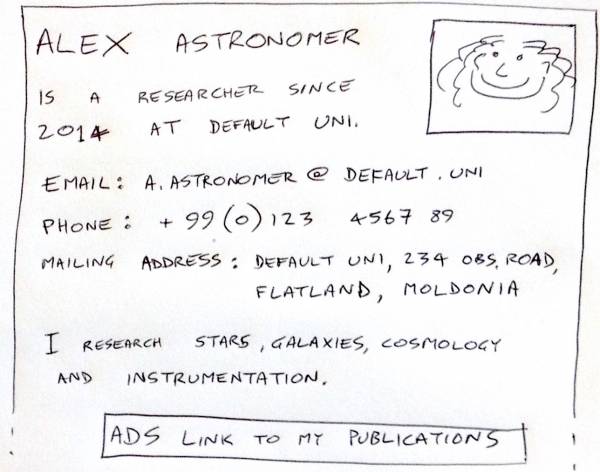

Minimal Webpage

Put your full name, then a sentence that says what kind of scientist you are, and the date when you joined your current research institution. Then - not too far down the page - add your email, your work mailing address, and optionally a work phone number (either to your desk, or to the department front desk).

Things nice to add include (i) a paragraph summarising what you're interested in a link to the search for your papers on ADS - if your name collides with other astronomer's names, you can make an ADS Public Library page and add your papers to it manually (thanks David J. Wilson for the suggestion on his page!) (ii) Your ORCID iD - if you haven't got one, go sign up now (iii) Your latest preprints if not posted on arXiv yet, (iv) A recent photo of yourself.

Keep the page to a bare minimum. Don't add anything that you're not willing to maintain. Do not add IN CONSTRUCTION or TO BE FILLED IN LATER. Instead, just remove the section. Nothing says "I can't manage a simple web page" like a "COMING SOON" tag that's three years out of date.

Why bother?

"Come on," I hear you mutter whilst rolling your eyes, "it's 2016! Who on earth still reads web pages?"

Well, Google does. And that's kind of the whole point. People occasionally want to contact you in a professional capacity. And the first thing they do is type in:

"(Your Name) astronomer"

...into Google and then hit Return. If you don't have a current contact in the first page of results, then you've at best irritated them slightly, and at worst, stopped them from contacting you. And the worst possible scenario - they start really looking for you on social media sites...

Who wants to contact you?

Potential employers, collaborators, and people wanting to invite you for colloquium talks, for starters.

I have a personal issue with this last one - I organised colloquium talks for Leiden Observatory, and this meant getting in contact with other researchers. There were several people that we would have invited if I could have found their email address. Which I didn't.

"But why didn't you search arXiv or social media?"

In several cases I did, and oh boy people get up to all sorts of fun things when they're not acting in a professional capacity! It's amazing what photos are publically accessible when you do a bit of digging in search of an email address. Unless you have kept a tight rein on your social media, your non-professional life may be on public display.

"But that's not fair! My personal life is my own business!"

I absolutely agree with you. But if you are uncomfortable with a future employer seeing your big weekend at that music festival, (i) don't post the photos and (ii) go set your privacy settings in whatever social media you express yourself in. Yes, I know that other people can tag you in photos and that those show up, but there are privacy settings on nearly all social media that can stop that too.

The goal is to get a potential professional contact to get the professional page before they find out anything more surprising. Google's algorithms set precedence on web pages from educational domains, so try to get a web page put on your department's server.

"But my department doesn't allow that!"

Really? Are you sure? Have you checked with them on this? At a bare minimum, get a free blogging website account, and make a professional looking post with a simple, clean template. Github now has a service to host clean web pages using Markdown as a simple page writing language. Google will eventually find it and index it. Go and make a web page so that Google will find your professional persona, and potential future collaborators aren't tempted to go hunting in the wild side of the internet.

The first version was written in 2016 August.

Comments and suggestions to: Matthew Kenworthy

On backing up your research

...hard drives are cheaper than your data.

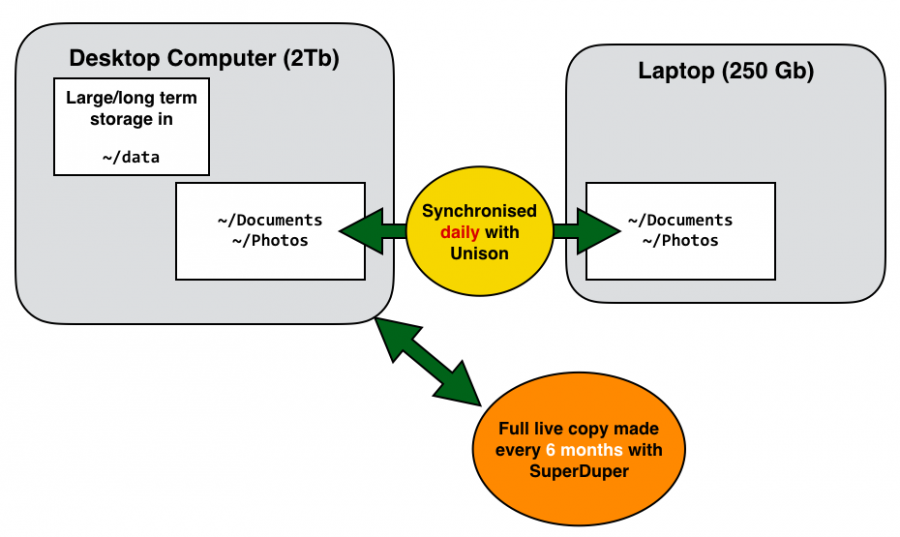

I have a desktop (which has 2Tb of storage but cannot travel) and a laptop (which I can use anywhere but has a small 250Gb hard drive). Keeping these two machines backed up without a lot of redundant data on either one was a source of ill-defined angst for me, and I was going cross eyed trying to remember what directory was the more up to date version and what to do about merging the results. It was a complete nightmare and led to many sleepless nights.

I stumbled on a method that works well, is simple to implement, and provides at least one backup if either my laptop dies or my desktop dies. I have two levels of backing up all of my work. I also regularly change where I work between the laptop and a desktop machine, both Apple machines. I use two pieces of software to do this: Unison file synchroniser - takes two directories on two separate machines (can be Windows and Mac or Linux) and makes them be identical copies of each other and SuperDuper!, a Mac program to make a complete bootable backup of your computer on an external hard disk.

Everything backed up every 6 months

My desktop has a 2 Tb drive, and everything I have done for work sits on this machine. Every 6 months or so, I buy a new hard drive, and plug it into an external USB hard drive case, and make a complete copy of the hard drive using SuperDuper! which makes a bootable version of my desktop machine.

It takes about 24 hours to duplicate my desktop machine. I then remove the drive and store it at home in the back of the shirt drawer. Currently a 2Tb hard drive is 80 Euros, so paying 160 Euros per year for a series of redundant backups makes sense to me.

If the desktop machine dies, or is lost in a fire, I have (at most) a 6 month old copy of all my data that I can immediately boot up on any other Apple computer and pull data off for that presentation tomorrow. But what about work since the last backup?

Backup every day

On my laptop and desktop, I keep the ~/Documents directory synchronised together. Depending on the day, I either work on the laptop or desktop machine, and then I run a synchroniser program that ensures both directories on both machines are updated with each other and completely identical.

To do this, I use the Unison File Synchroniser program, and I run it once in the morning when I arrive at work, and again at the end of the work day. In this way, I never lose more than a day's work to a hardware failure.

The only data that is never backed up are the directories in my laptop's home directory that are not in Documents, so that's where I put all my test scripts or temporary dumps of data. When I'm ready, I move stuff I want to keep into the ~/Documents directory and run the synchroniser. In this way, I can keep the very large data directories on my desktop machine outside the Documents folder, and drag a copy of them into Documents when I need access to the data on my laptop. I only have to remember to edit stuff in ''Documents'', and within 1 day, it has a backup on the other computer.

Laptop gone? Get a new laptop, download the synchroniser, and pull over the copy of Documents. Desktop dies? Duplicate the hard drive into the new desktop, then run synchroniser from the laptop to repopulate Documents.

You always have two live copies of your recent work, and then you can move inactive directories out of the desktop Documents just before your 6 month big backup. This method has worked successfully and transparently for me for over five years, with one time where I did a full resinstall successfully.

Written 01 September 2016 inspired by a tweet from @IamSciComm and @StellarPlanet

On Being Professional

...acting responsibly and being reliable collaborator

(In conversation with Dr. L. Morabito in August 2016, and by e-mail from Prof. J. Wright in February 2017)

The popular image of a scientist implies that they're forgetful, prone to ignoring meetings that they consider irrelevant to the Big Idea they're working on this week, and that people will put up with them indefinitely because they produce results right when they're needed.

In reality, this is not true. To be a successful scientist, you have to be professional. What we mean by this is that you should be respectful of other people's time and commitments. By ignoring messages, failing to turn up promptly to arranged meetings, and not delivering work, you give the impression that you are unreliable.

Attitudes that are tolerated in academia (for better or worse) are not tolerated in the business world, where missed deadlines cost companies money (and shortly thereafter your job).

To this end, you should:

- Be on time. That means you are in your chair ready to go at the scheduled start, not walking in the room.

- Keep regular working hours. Even if you come in at 3pm and work till 11pm, you need to be consistent so if people are looking for you, they know what to expect.

- Be considerate of other peoples' busy schedules. Don't say "this will take 15 minutes" and then take an hour. Respect any time limit they offer if you are walking into their office unannounced.

- Always be clear about expectations: yours or others' expectations of you. People are not mind readers.

- If your boss asks you to do something, it's generally a good idea to do it.

- If someone gives you a deadline, and you absolutely cannot meet it, let them know beforehand and tell them why.

More specifically for science researchers:

- Always attend colloquium, even if it's not your field.

- Always attend group meetings. You may find them boring, but the meeting is not all about you, and your presence adds to the meeting for other people. Plus, you never know when something useful will come up.

Additional suggestions by Jason Wright (Feb 2017):

- Be respectful to colleagues both above and below you - The administrative assistants, custodians and other staff are not your personal assistants.

- Treat them with respect - thank them when they've gone above and beyond their remit, and apologise when you've made mistakes.

- Be aware you are a role model - Your behaviour and attitude to colleagues are noticed by others, especially less senior researchers.

- Participate in department social functions - your department is more than the sum of the researchers. There is an additional social level to any group of colleagues working together.

- Encourage professional interactions - avoid generating an Old Boys Club or frat house atmosphere, encourage participation in coffee break discussions.

- Don't gossip or backbite, apologise if you are rude to others - Astronomy is a small, well connected group of scientists. Word gets around very quickly.

Keep in mind that although as a student and scientist you are learning to operate independently, you will not succeed long-term in science if you cannot show that you will be a good collaborator. That means people need to see you are reliable and take things other than your own work seriously.

On managing your time

...because you cannot buy it.

Based on notes from Laura Kreidberg (Oct 2020)

Time is your most valuable resource - it's the one thing that you know you will run out of. You have 24 hours per day, and removing sleep, eating, exercise and travel, you have around 40 work hours per week, about 2000 hours per year, about 60000 hours during your working life. It goes faster than you think.

- Use a calendar When you are asked to do task X, put time to do it on your calendar rather than adding it to a TODO list. For open ended projects, block off chunks of time for "writing" or "data reduction".

- If you are invited to do something N months in the future, pretend it's next month If you don't have time to do it, then say no! Your future self will thank you for not over-scheduling.

- Figure out when you're most productive in the day, and plan your workday accordingly Save simpler takes for "slump time" when you don't need full concentration.

- Use a time management system I highly recommend Getting Things Done (GTD) by David Allen.

On Watching a Meteor Shower

...if you're really insisting on doing it.

Meteor showers can be one of the most challenging astronomical events to watch without a little preparation. They are small pieces of interplanetary (or even interstellar) rock that hit the Earth's upper atmosphere at several tens of kilometres per second and are heated up by air friction so that they glow brightly, disintegrating in a second or less.

It's easy to get frustrated if you're not prepared. If nothing else:

- Dress warmly so that you won't get cold standing still outside for 20 minutes

- Lie back so that you can comfortably look up and see as much of the sky as possible

First, check outside - if it's cloudy, you won't see meteors. They usually burn up far above the cloud layer.

Second, dress up warmly, with more clothing than you would need if you were going for a walk, and preferably a warm hat to cover your ears. You will be lying back and looking up at the sky for tens of minutes, and you will feel the cold, even with a small breeze.

Lie back and look up so that you see as much of the sky in your field of view. A reclining chair with neck support is ideal, but lying on the ground will do as well.

Meteors appear as a fast moving point of light that takes about one second to appear and disappear, crossing up to half the sky - see this compilation of meteors as seen by a camera in Brazil.

They appear randomly across the sky at irregular intervals, and their numbers can vary from a few to several dozen per hour during annual meteor showers (see EarthSky's Guide to Meteor Showers during the year). Patience is key here!

Dark skies with no moon in the sky are the best conditions, but it's possible to see them in brighter skies near cities too.

If you are patient and give it at least twenty minutes, then you should be lucky enough to see these tiny pieces of extraterrestrial dust shine briefly in the night sky.

Last updated around May 2018.